Evaluation of the European Capital of Culture Bad Ischl Salzkammergut 2024

The European Capital of Culture Bad Ischl Salzkammergut 2024 (ECoC24A) was innovative in several key respects. It represented the first inner-Alpine, rural region to hold the title, operating under conditions markedly different from those of both smaller towns and larger urban centres. At the same time, the region is characterised by a long-established cultural identity and a strong tourism profile. While these factors created considerable opportunities, they also posed structural challenges for the design and delivery of a Capital of Culture programme. In addition, the SROI analysis presented here was itself a novel undertaking. Adopting a broad, stakeholder-oriented understanding of social value and grounding it in empirical micro-level data is a demanding task, particularly in the context of a European Capital of Culture (ECoC), where impacts extend across a wide range of stakeholder groups.

Given constraints in time and financial resources, a partial SROI analysis was therefore conducted, focusing on the identification, quantification and monetisation of impacts for five key stakeholder groups. Despite these limitations, the study represents the first comprehensive, empirically based assessment of the short-term social value generated by a European Capital of Culture from a microdata-driven, stakeholder-focused perspective.

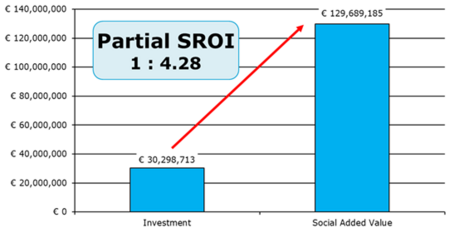

The central finding of the analysis is a partial SROI ratio of 4.28, indicating that each euro invested generated a monetised social value of €4.28. Sensitivity analyses produced a range from €2.94 to €7.02 per euro invested.

The analysis compares the financial input for ECoC24A, amounting to approximately €30.3 million – modest by ECoC standards – with 51 quantified and monetised impacts across the five core stakeholder groups, yielding a total value of €129.7 million. These impacts are rooted in the extensive programme delivered by ECoC24A, which comprised 314 projects, including 117 associated projects.

The greatest share of benefits accrued to the regional population. An added value of over €42 million highlights the breadth of socio-cultural effects generated. Notable outcomes include a stronger sense of regional cohesion, heightened interest in arts and culture, entertainment value, and improved access to cultural offerings. At the same time, negative impacts were identified, such as frustration over perceived insufficient regional involvement and the emergence of social tensions. Overall, however, positive impacts clearly outweighed negative ones, resulting in an average added value of €388 per resident.

Project participants and artists also experienced substantial impacts, with a combined value of approximately €31 million. Particularly significant were increased visibility, enhanced opportunities for artistic experimentation, greater income stability, and intensified cooperation and networking. A major negative impact was the high level of stress and exhaustion associated with the intensity of project work, a challenge also observed in other Capitals of Culture.

The impacts also extended beyond the project participants to the whole regional cultural scene. With around €9.5 million, it benefited in particular from infrastructural impulses, increased artistic and cultural diversity, and increased visibility. At the same time, funding gaps outside the ECoC24A and a certain degree of post-festival fatigue hampered short-term developments outside the ECoC24A projects. The modest assessment of ECoC24A by parts of the regional cultural scene, as revealed in survey data, points to unrealised potential and ongoing structural challenges within the region’s cultural ecosystem.

Although economic impacts are not the primary objective of a European Capital of Culture, they remain highly relevant at both regional and national levels. Cultural tourism, which plays a central role in this context, was therefore included in the SROI analysis.

Tourists experienced an estimated added value of around €29 million, driven by increased cultural engagement, entertainment, educational impulses and a heightened awareness of European values. Negative impacts, such as rising accommodation prices, were found to be marginal. The analysis also shows, however, that many tourism-related impacts can only be partially attributed to ECoC24A, as a significant share of visitors consisted of culturally motivated tourists who would likely have participated in cultural activities regardless. This results in an average added value of €165 per tourist.

The tourism businesses benefited primarily from increased visitor numbers, translating into a financial added value of approximately €14 million and a total social added value of around €18 million for this stakeholder group. Additional positive impacts included momentum towards more sustainable tourism practices and a more diversified visitor profile. Minor challenges arose from temporary capacity pressures linked to atypical visitor structure.

Overall, the partial SROI analysis shows that around two-thirds of the added social value created remained in the region. When interpreting the SROI ratio of 4.28, it should be borne in mind that the analysis covers only five of a total of 18 identified stakeholder and impact groups. In line with common practice in SROI studies, the focus was placed on the most influential stakeholders. A cautious interpretation, which consistently accounts for negative impacts, suggests that a full SROI would likely yield a higher value.

At the same time, regional characteristics had a dampening effect on the partial SROI result. The Salzkammergut, with Bad Ischl as its flagship town, is a region with a strong identity, a long-standing tourism orientation and an already rich cultural offer. These conditions make it more challenging to introduce new artistic impulses, stimulate cultural innovation or generate additional tourism-related value without encountering resistance from parts of the local population. A comprehensive impact analysis such as SROI must take these contextual factors into account, which in turn dampens the measured added value. Against this backdrop, the SROI ratio of 4.28 can be regarded as a robust and conservatively estimated result.